The world has been shocked by the beheadings of two American journalists, James Foley and Steven Sotloff, by ISIS in Syria.

These horrific killings were especially shocking to those of us fortunate enough to have called James and Steven our friends.

I have spoken at length about James and Steven in the media in recent weeks to help their legacy and tell the world what they died for, but I want to write this blog as a tribute to these two great men. It is important that we never forget them, why they were in Syria, and what they gave their lives for.

James Foley

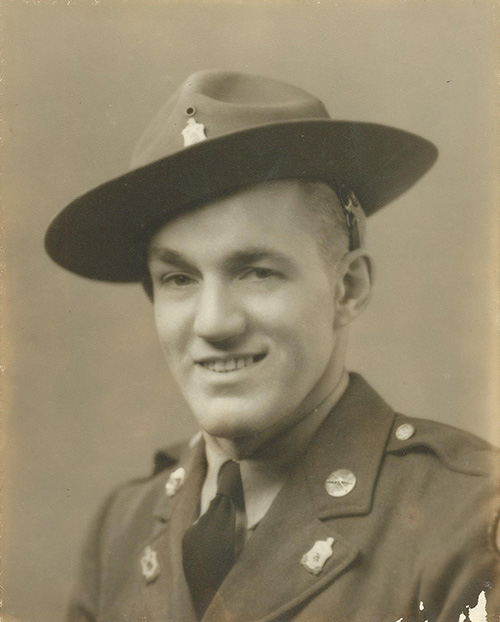

Matthew VanDyke, Nouri Fonas, Clare Morgana Gillis, and James Foley in Nouri Fonas’ home in Benghazi, Libya. November, 2011.

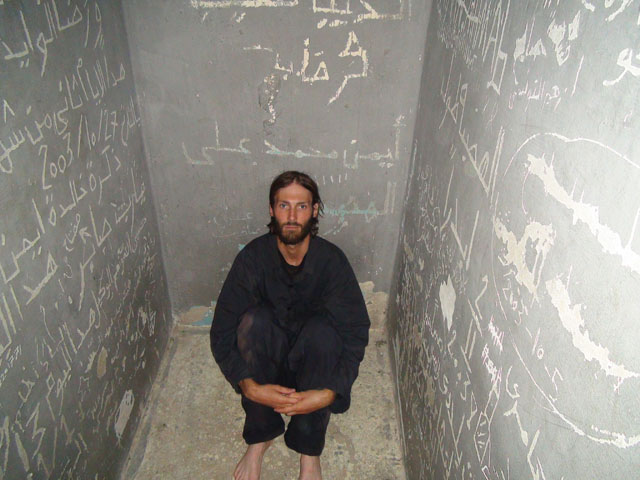

My friendships with James and Steven both began in Libya. I first met James in 2011 a few days after I escaped from Abu Salim Prison. James had returned to Libya a few months after his release from a Libyan prison where he was held for 44 days, captured near Brega with journalists Clare Morgana Gillis and Manu Brabu. A fourth journalist, Anton Hammerl, was with them before they were captured but was killed by Gaddafi’s forces.

The Foley family had been in touch with my family when I was missing in action in Libya as a prisoner of war, and James’ uncle had helped create the Free Matthew VanDyke Facebook page for my family. We had heard of each other from our families before we ever met that day in the Corinthia Hotel in Tripoli.

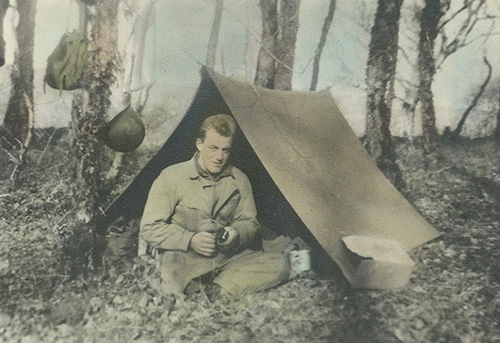

We became friends over swapping prison stories about our time as guests of Colonel Gaddafi. James, like most of the journalists in Tripoli at that time, did not have a room at the Corinthia Hotel and was sleeping in the lobby, so when the NTC (the rebel government) gave me a room at the Corinthia, I invited James to take the second bed as my roommate. We were later joined by two other journalists, Jonathan Pedneault and Saad Basir.

We were roommates for about a week, while I waited for my Libyan friend, NourI Fonas, to reach Tripoli so I could return with him to combat on the front lines. During this time I gave James a tour of my prison cell at Abu Salim Prison, and he filed an excellent report for GlobalPost. Soon after, I returned to combat on the front line.

During the war, Nouri and I would sometimes take journalists with us to the front line so they could report on the war while we were fighting. This was safer for them than jumping in a random vehicle because Nouri was a good driver and I was on the gun, and we did proper recon of the route, taking precautions that some other vehicles did not.

Among the many journalists we took or escorted to the front line was James Foley, during which time I got to see him in action as a journalist. He was courageous, smart, and had a way with people that instantly attracted them to him. The Libyans loved him.

Journalist James Foley riding in Matthew VanDyke’s KADDB Desert Iris 4×4 vehicle in Libya during the Libyan Revolution (October, 2011)

I would see this again a year later in Aleppo, Syria. When I arrived in Aleppo, Syrians were asking me if I knew James Foley and when he would return. He had made an incredible impression on them just by being himself. The Syrians too, loved him.

James arrived a few weeks later and we went out into the streets of Aleppo with three other journalists. James was filming and reporting for GlobalPost and I was making my film Not Anymore: A Story of Revolution. Together we ran across streets to avoid snipers, talked to local fighters and civilians, and filmed the war. It was like old times, only I was behind a camera this time instead of a gun, and we filmed each other as we had in Libya as well.

James Foley, Matthew VanDyke, and Omar Hattab in Aleppo, Syria (October, 2012)

The footage from that day is some of the last of James Foley alive. A little over two weeks later he disappeared in another part of Syria.

I never saw him again.

Steven Sotloff

I first met Steven in Libya in 2012, on my way back from filming Not Anymore: A Story of Revolution in Syria. I was in Tripoli to give a speech at the Libya Summit when Steven contacted me offering to mediate a dispute between myself and a mutual Libyan friend. I had never met Steven before, but accepted his offer. Steven successfully worked things out between the Libyan and I, and after that somewhat unusual first meeting we became good friends.

Steven, like myself, was a North Africa and Middle East specialist. He had learned Arabic, appreciated the culture, made many friends and contacts in the region, and had an affinity for the subjects he was reporting on. He wasn’t one of those journalists who jumps from warzone to warzone. Steven really cared about Libya and Syria and the plight of the people in these countries, and he was driven to bring their stories to the world.

Steven and I would often talk about security in Syria and what was going on behind the scenes in Aleppo. He was fully aware of the risks and did what he could to reduce them. We met for dinner in Washington, DC along with some Syrian activists and my girlfriend Lauren Fischer, and discussed his upcoming trip to Syria. We also talked about the disappearance of James Foley.

This was the last time I saw him, and I wish I had taken a photo of us.

A few weeks later, Steven was kidnapped in Syria.

Legacy

What made James Foley and Steven Sotloff such great men and such great journalists? They cared. They weren’t covering stories, they were covering people. When James Foley saw that Dar Shifaa Hospital didn’t have an ambulance, he held a fundraiser to buy one for the hospital. When Steven Sotloff decided to report from the Arab world, he took the time to learn Arabic, understand the culture, make connections, and truly understand the region he was covering, taking on additional risks as a dual-nationality American-Israeli so that he could do the best job possible.

They went the extra mile. They cared. And the people whose stories they were telling knew it and they loved both of these men.

The loss of these two great men, whom I am truly blessed to have known, was not in vain. Their legacy will endure in the memories of their family, friends, colleagues, the people in the regions they covered, and in the masterful journalism that both left behind for eternity.

Their deaths have catalyzed an international response against the barbarity and cruelty of ISIS which will lead to the destruction of this scourge on humanity. Their deaths will lead to the liberation of millions who have suffered under the rule of the Islamic State and have an impact on world history.

The man who killed them thought that he was ending their lives, but he was wrong. In death James Foley and Steven Sotloff have achieved immortality, and their legacy will endure forever.