The Tuareg Rebellion in Mali

(also available in French here)

Matthew VanDyke wearing a Tuareg tagelmust in the Sahara desert

I admittedly had some mixed feelings when deciding whether to write about the Tuareg rebellion because of my experience as a freedom fighter in the Libyan civil war. Thousands of Tuaregs were serving in Muammar Gaddafi’s army during the Libyan civil war and others went to Libya as mercenaries to join them. If I had encountered any of them on the battlefield they would have been in my crosshairs like any other Gaddafi fighter.

But I never saw a Tuareg during the war and with good reason. Most had already fled back to Mali before I escaped from prison and returned to the front lines. They weren’t Gaddafi loyalists, they were Gaddafi opportunists – they came for money – and while I consider this even more deplorable than actually believing in Gaddafi and being a true loyalist, it at least suggests that their participation in the Libyan civil war was morally but not ideologically corrupt.

The Tuareg desire for self-determination cannot be dismissed despite the desire of many to do so for the past hundred years. This is a conflict that has been ongoing since 1962 and is just the latest of four Taureg rebellions in Mali. The Tuareg, the fabled Blue Men of the Desert, have demonstrated repeatedly that they won’t disappear quietly into the Sahara.

The current Tuareg rebellion, by far the most organized, equipped, and successful of them all, has given the Tuaregs the best opportunity for self-determination that they have ever had. They may never be in this position again, flush with arms and ammunition and their ranks dominated by veteran fighters returning from war in a neighboring country. The military wing of the movement, the National Movement for the Liberation of Azawad(MNLA), has learned the mistakes of past Tuareg rebellions and will not repeat them. This time they have also learned some lessons of the Arab Spring and are supported by a virtual army of Tuareg activists around the world who use social media to communicate, coordinate, and propagandize the conflict to carry it far beyond the sands of the Sahara.

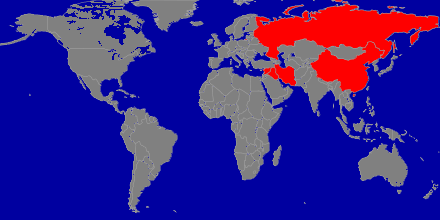

Azawad Calling

The Tuareg want to establish their own country, Azawad, in northern Mali. Their traditional homeland in the Sahara was carved apart by the French during the Scramble for Africa and divided among Mali, Niger and Algeria, all of whose borders were carefully drawn by France to pursue its own interests in Africa. The Tuareg of Mali, a nomadic desert people, were lumped into a country twice the size of France and quickly fell under the dominance of their former slaves, the black Africans living in tropical Mali south of the Niger River. Like many of the colonial borders drawn in Africa, the Middle East, and Asia by European powers in the 19th and 20th centuries during the period of New Imperialism Mali was destined for perpetual strife.

Unlike many other intrastate conflicts, the Tuareg aren’t fighting for resources or valuable land. The conflict is primarily ideological, a matter of cultural pride to a people with simple needs and interests. Mali is already one of the poorest countries in the world and Azawad would be even poorer, at least for the first several years. However, the geology of the Taoudeni Basin in northern Mali suggests that significant oil and gas reserves may lay beneath the sand. Companies have been unable to conduct adequate surveys of the area due to poor security in the region, but there is little doubt that there is enough oil to allow Azawad to survive as an independent nation. Cynical observers with no sense of history have suggested that those oil reserves are behind the current rebellion, an argument that doesn’t stand when one considers that the Tuareg have been fighting for independence in Mali for 50 years.

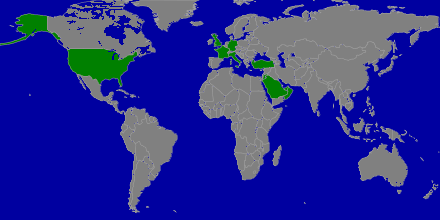

Resistance by the West, Mali, and its Neighbors

The arguments in favor of preserving Mali’s territorial integrity at the expense of the Tuaregs are difficult to justify. The West’s primary interest in Mali is fighting Al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM) and preserving Mali’s 20 year history as a democratic country and stabilizing force in West Africa. Mali is active in several programs, initiatives, and organizations in the region and has been a valued and reliable partner of the West. The US and EU are also concerned that unrest in Mali could spread and that a lack of central authority in the Azawad region could lead to a safe haven for Al Qaeda as existed in Afghanistan prior to 2001.

Algeria and Niger believe that the creation of Azawad would incite Taureg rebellions in their own countries (and in the case of Algeria, perhaps a Tuareg-inspired Berber rebellion as well). This is similar to the arguments made by Turkey and Iran about Kurdish independence – that it would inspire the Kurds in their own countries to also seek independence. Like Turkey and Iran, Algeria and Niger will do everything they can to crush the aspirations for self-determination in a neighboring country in the pursuit of crushing them at home.

The government of Mali is panicked, despite enjoying the overwhelming support of non-Tuareg Malians (and a limited number of Tuaregs as well). The Tuareg rebellion has been so successful that it prompted a coup d’etat by military officers desperate to stop it, ending 20 years of democracy in Mali. The Malian government and most of its citizens believe that preserving their multi-ethnic, territorially vast, democratic country is in the best interest of everyone. They also don’t want to lose whatever natural resources might lay hidden beneath the sands of northern Mali.

Intelligence and Policy Failure

The scandal in all of this was that the Tuareg insurgency of 2012 was entirely predictable and could have been prevented by Mali and its allies. Tuareg fighters were able to haul a massive arsenal of weapons and ammunition over a thousand miles from Libya to Mali, through Algeria or Niger, without interference by Mali’s allies in the West, Algeria, or the Malian government. It was an extraordinary display of incompetence by all involved.

That a Tuareg insurgency would follow the Libyan civil war was entirely predictable. The Mali civil war (1990-96) was begun by Tuareg fighters supported by Libya, including Tauregs who returned to Mali after serving Gaddafi in his war against Chad. A veteran of the civil war, Ag Bahanga, led the failed 2006 uprising and was forced to flee to Libya in 2009. He became a close confident of Muammar Gaddafi. Another Tuareg leader, Mohammed Ag Najm, became a commander of one of Gaddafi’s elite desert units, and many Tuaregs enlisted in the Libyan army.

Bahanga and Najm waited for their opportunity to act. Once the Libyan civil war began to turn against Gaddafi in early summer 2011 Bahanga and Najm led the Tuaregs to raid the arms depots and then headed southwest back to Mali. They were in command of elite desert units that had the men, equipment, and knowledge of the desert necessary to transport their massive stockpile of weapons over a thousand miles through three countries. It was a time-consuming and difficult operation that allegedly took several trips over a period of months and is rumored to have had the consent of the Libyan rebel government (the NTC) because it reduced Gaddafi’s arsenal and took Tuaregs off the battlefield.

The United States clearly had an interest in preventing this through either direct action or by coordinating with the Algerian or Niger authorities to stop it, especially since Bahanga and Najm’s arsenal may have included surface to air missiles.

Once again the US intelligence community has dropped the ball despite overwhelming technology and funding simply because they lacked the ability to think a few steps ahead and have the wrong people (with the wrong type of experience) working as analysts.

What happens next?

This time the proverbial genie is out of the bottle and it isn’t getting put back. The Mali government strategy, if one can call it that, appears limited to waiting for the Tuaregs to run out of ammunition. This is unlikely to happen anytime soon as the MNLA will successfully negotiate for the surrender of towns and garrisons as they proceed south and capture the weapons left behind. Tuareg soldiers from the Malian army have also defected to the rebels bringing with them vehicles, weapons, and ammunition.

The coup d’etat, intended by the conspirators to better enable the military to crush the rebellion, will at least for now have the opposite effect. The government is weaker than ever, which will hurt the morale of government forces and lead to more surrenders and defections from army ranks.

Years of cooperation between the US and Malian government are going down the drain and analysts are typing away on their keyboards generating assessments of what the latest Tuareg rebellion means to the United States and the War on Terrorism. A determination will likely be made that short-term regional stability trumps all other concerns, as usual; even the right to self-determination which is part of our national ethos.

The State Department will frantically start pulling the levers of diplomacy to find a negotiated solution to end the conflict – a negotiated solution that will certainly not allow for the creation of Azawad as a new country. The US military may even cooperate with the Malian military to crush the rebellion which will do far more than anything to push Tuaregs, who have historically shown little affinity for AQIM, straight to their neighborhood jihadi recruitment office.

Red, White, and Blue Men of the Desert?

The current situation presents a historic opportunity for the United States. The coup d’etat was counterintuitively fortuitous by giving the US government an excuse to withhold support for the Malian government. This will provide more time to assess the situation, avoid angering the Tuaregs, lessen AQIM’s ability to capitalize on the insurgency with propaganda against the West, send the message that coup d’etats against democratic governments will not be tolerated, help the US walk the fine line of not angering Algeria and Niger, and most importantly allow the Tuaregs to achieve their goal of establishing Azawad.

How is the creation of Azawad possibly in the interest of the United States? The time to stop this from happening was when Bahanga and Najm set off from Libya. Tracking their movements and having the Algerians stop them, or alternatively, making sure those convoys mysteriously disappeared in the desert with nothing but charred, smoking wrecks of vehicles left behind, would have solved this before it started. Now, it is too late.

Within the next few weeks Kidal, Gao, and Timbuktu will fall to the Tuaregs. With the acquisition of the three capitals of the three regions that will compose Azawad the territorial aspirations of the Tuaregs will be largely complete. Entrenched in favorable terrain and enjoying the support of the local population, the Tuaregs can defend Kidal, Gao, and Timbuktu against any counter-offensive by Mali’s small army of 7,000 (now likely only 4,500 if estimates of casualties and desertions are accurate).

The war is lost.

If policymakers in Washington have learned anything from the Arab Spring (and they appear to be learning, slowly) they should realize this and will soon begin tapping every connection they have with the Tuaregs to convince them to stop at the Niger River, to negotiate a ceasefire with Mali, and to guide the Tuareg leadership towards democracy, self-governance, and further cooperation with the US against AQIM in exchange for political and economic support. They’ll push for the federal solution to the conflict that grants the Tuaregs semi-autonomy over northern Mali, which might not be acceptable to either side. The Tuaregs have been burned before by the Malian government refusing to honor the terms of previous agreements.

The US government will be reluctant to support the creation of Azawad as a new country. Those working at the State Department, Pentagon, and the intelligence agencies have never understood this part of the world, as revealed by Wikileaks documents on Mali. A career government analyst will have a hard time wrapping his head around how dispersed desert nomads would be better partners in the fight against AQIM than the government of Mali.

The reason why should be obvious even to those who haven’t spent time among the people of the Sahara. Mali has never had any real control over the Azawad territories. The Tuaregs are culturally, racially, and politically foreign to the central government, and the Sahara is hostile territory to the vast majority of Malians. They have never been able to tame it, understand it, or function in it. Mali was never going to be a truly effective partner against AQIM.

Azawad, on the other hand, will be. Nobody knows the desert better than the Tuaregs. They have lived there for two thousand years, know every route and every track in the desert, are connected by tribal and family ties that make it impossible for someone to join AQIM without others knowing, and most importantly have shown little desire for either radical Islam or terrorism in the past. The MNLA has made it very clear that they intend to create a secular, democratic state. With no history of radical Islamism, the majority of Tuaregs opposed to the imposition of sharia law, and a matrilineal society that respects the rights of women, there is no reason to doubt their intentions.

Most importantly for the United States, the Tuareg are the only people who can effectively police that region of the world, and since the Tuaregs are dispersed over 5+ nations their reach and potential as a partner in the War on Terrorism should not be underestimated.

The Sahara is their sandbox, and they know everyone who plays in it.

Fighting AQIM is the only significant strategic interest the United States has in this fight, other than maintaining good relations with Algeria and Niger or preventing instability from spreading beyond Mali’s borders. Every effort should be made to reach out to the Tuaregs and gain influence and favor with them to ensure that the United States has influence in Azawad when this war is over.

It won’t be easy. The Tuareg are fiercely proud and independent. Whatever we do they won’t ever love us – they even fight among themselves. They’ll always question our intentions and the Sahara is notorious for conspiracy theories that will only bolster their suspicions. However, the Tuareg relationship with Gaddafi should serve as a model for a US-Azawad relationship.

The Tuareg can be bought. They have replaced their ancient camel caravans transporting salt across the Sahara with Toyota pickup trucks smuggling cocaine, weapons, and migrants. They’ve been involved in kidnapping foreigners for sale or ransom. Corruption and criminality have spread among the Tuaregs as the Mali and Niger governments have failed to integrate them into modernity and the rest of society. When Gaddafi stepped into this void by funding development projects, employing Tuaregs in his armed forces, declaring support for a Tuareg state, and identifying himself with the Tuareg by sleeping in tents and various other displays of tacky showmanship, the people loved him for it.

Therein lies an opportunity for the United States. Obama doesn’t need to sleep in a tent, but supporting the Tuareg’s Azawad aspirations would go a long way if accompanied by economic development projects. Stepping into the void left by the removal of Gaddafi would position the United States to have real influence in the region and monitor a part of the world that is often obscured in darkness.

This might be achievable through the likely outcome of this war: the federal solution of Tuareg semi-autonomy in Azawad, while remaining part of Mali. This would resemble the situation of Kurdistan in Iraq and might satisfy enough Tuaregs to take the steam out of their rebellion. Regardless of whether the Tuaregs achieve semi-autonomy or independence (and one of these outcomes will be the result of this successful rebellion) the United States must position itself as a friend of the Tuaregs and aggressively support the region with aid and development to buy the support of the people.

The United States cannot risk Azawad resembling Afghanistan pre-2001, where American reach was so limited that Al Qaeda was able to operate with impunity. If the US reaches out to the Tuaregs now we will gain influence over the emerging Azawad government and create bonds that could be among our most significant victories in the fight against Al Qaeda.

Like this:

Like Loading...