The Syria Game

The leader of al-Qaeda, Ayman al-Zawahiri, recently called on Al-Qaeda fighters to join the revolution in Syria and help overthrow Bashar al-Assad. That the United States and al-Qaeda find themselves on the same side in Syria highlights the complexity of the conflict.

Syria is about more than just Syria. Its geographic location, ethnic and religious divisions, ties to Iran and Hezbollah, influence in Lebanon, relationships with Russia and China, vast chemical weapons program, conflict with Israel, and pivotal role in the Arab Spring movement has made it the center of a geopolitical struggle that extends far beyond Syria’s borders.

The Syrian Civil War is well on its way to becoming a proxy war, much like the Lebanese Civil War of the 1970s and 80s. It is also part of a larger strategic rivalry between East and West, much like The Great Game between the British and Russian Empires in Central Asia during the 19th and 20th centuries.

The players in this new Great Game in Syria have chosen their sides and have enough at stake that they’ll do almost anything to win.

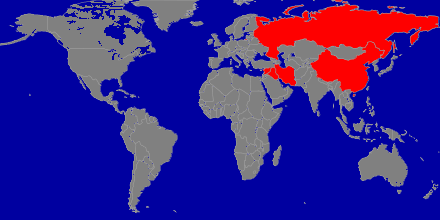

Team Assad

The most influential countries supporting the regime of Bashar al-Assad

Russia and China

Russia is engaged in a desperate bid for survival and relevancy in a rapidly changing world. It has declined from a world superpower to a flawed, corrupt, quasi-democratic, largely dysfunctional shadow of its former self that is desperately grasping at spheres of influence that are steadily shrinking away. Most of these spheres of influence are in the Arab world, Asia, and Africa, where the Russians maintain significant economic and military interests. In Syria, these include billions of dollars in defense contracts and Russia’s only Mediterranean naval base (at the Syrian port of Tartus.)

China is a rising power with similar economic and military interests in Syria. More importantly, both Russia and China realize that the Arab Spring is just the beginning of a wave of revolutions likely to spread across the globe, and that eventually the Arab Spring will morph into a Russian and Chinese Spring that will land at their doorsteps. They will do whatever they can, from obstructing the United Nations to advising, arming, and supporting authoritarian regimes, in order to slow the advance of democracy around the world.

Iran

Iran and Syria have an extremely close relationship that has endured for over 30 years. They are both ruled by Shia Muslims, are opponents of Israel, and provide funding and weapons to Hezbollah in Lebanon. Iran will do everything in its power to prevent the fall of the Assad regime because it would eliminate their strongest Arab ally, choke off Hezbollah, deny them territory from which to launch attacks against Israel, and drastically reduce Iranian influence in the Arab Middle East. Iran also fears that once Syria falls, Iran will be among the next countries to experience a popular uprising that threatens their own regime.

Iraq

Iraq, run by a Shia-dominated government that maintains a close relationship with Iran, has supported Assad throughout the uprising. Iraq fears that a civil war punctuated by sectarian conflict between Shia and Sunni could spill over the border and reignite more serious problems in Iraq. There is no doubt that close ties with Iran also guide their support of the Assad regime.

Hezbollah

Hezbollah receives support from Syria, and funding and weapons from Iran. The removal of Assad would be devastating to them, and if it paved the way for regime change in Iran as well, the organization would be unlikely to survive.

Lebanon

Hezbollah’s political alliance, “March 8,” has been the ruling coalition in Lebanon since 2011. Although the rival “March 14” Alliance and the majority of Lebanon’s population support the uprising against Assad, Hezbollah will use their political power to keep Lebanon in Assad’s corner, or at least on the sidelines.

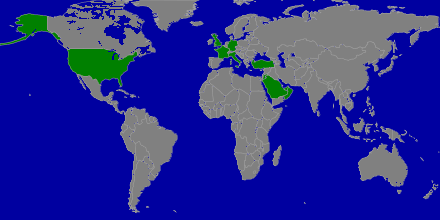

Team Free Syrian Army

The most influential countries supporting the Free Syrian Army

The West

The United States and Europe are driven by a belief in democracy and human rights. Although they have turned a blind eye to many protest movements in the past and considered regional stability their main priority (as evidenced by the tepid response to Egypt’s uprising against Mubarak), public outcry driven by social media has combined with a realization that the Arab Spring is unstoppable and that their political, economic, and strategic interests are best served by allying with the winning side (the revolutionaries) who will form the governments of the future.

The United States and Europe also want to remove Assad because it would severely weaken Iran strategically and politically. Regime change in Syria, combined with economic sanctions, the covert war currently being waged against Iran, and the likelihood that Iranian nuclear facilities will be bombed within the next year, could help incite an Iranian Spring and the downfall of the regime.

The West’s enthusiasm for the revolution in Syria is nevertheless tempered by concerns that a militarized, post-Assad Syria could result in a failed state that would be disastrous for regional security, especially for the security of Israel. The fact that Syria has one of the largest chemical weapons programs in the world and the likelihood that some of these weapons will end up in the hands of terrorists after the war ends dramatically exacerbates those concerns.

Al-Qaeda

Assad’s regime is among several secular governments in the Middle East that have long been on al-Qaeda’s target list. They are especially motivated to fight since Assad and his regime are Alawite Shia Muslims, considered heretics by al-Qaeda. Al-Qaeda views Syria as an opportunity to join the right side of a popular revolution, and by doing so gain popularity and new recruits, weapons, and influence. The overthrow of Assad is also central to their belief system, as the Islamic faith mandates helping oppressed Muslims.

Turkey

Turkey has no interest in a protracted, years-long civil war on its border. But the calculations that led them to provide sanctuary to the Free Syrian Army run much deeper. Turkey has had a contentious relationship with Syria and Iran over their neighbors’ sponsorship of Kurdish PKK insurgents who are fighting Turkey’s government. Turkey now sees an opportunity to cut off the PKK’s funding and supply lines by removing Assad from power. They have gone all-in on the Syrian uprising, as an Assad victory would be a significant boost to the PKK, and result in a contentious relationship that could impact regional trade for years.

The GCC

The Gulf Cooperation Council, with Saudi Arabia and Qatar as its most vocal critics of Assad, is siding with the Syrian protestors because the majority of them are Sunni, and because they want good relations with the new government after Assad falls. They also want to weaken Iran. While it may seem hypocritical for the authoritarian regimes of the GCC to be supporting popular uprisings, they have calculated that it is better to be seen as supportive of the Arab Spring, thereby diminishing calls for reform in their own countries.

The Game Has Begun…

All of these players in the Syrian game make the debate about foreign intervention rather meaningless. Foreign intervention is already taking place. The United Nations has been rendered useless by Russian and Chinese obstructionism, and the game is now being played through covert action, supplying weapons to the rebels, and diplomatic maneuvering. The players of this game intend to win at almost any cost. Although the outcome of the Syrian Civil War appears to favor the downfall of Bashar al-Assad, the amount of time it takes and the number of lives that are lost will be largely dependent on who plays the game the best.

The Lebanese Civil War should serve as a cautionary tale for foreign intervention in Syria. That proxy war lasted 15 years with over 1 million killed or wounded. The similar demographics and sectarian divisions in Syria virtually ensure a repeat scenario if the international community plays the game the same way in Lebanon.

The countries that support a free Syria must intervene in an unambiguous, direct way that signals a full commitment to the removal of Assad. The Syrian rebels must consolidate under the banner of the Free Syrian Army. Once they have done this, they must be well-equipped with all of the weapons, ammunition, intelligence, and supplies needed to defeat Assad as quickly as possible.

Foreign intervention in Libya helped us win the war far more quickly and with fewer casualties than would have been possible on our own. The NATO campaign was not only strategically important, but it signaled an international commitment to the removal of Gaddafi that led to far more Libyans joining the rebel ranks. Once this happened, we were unstoppable.

The international community has the ability, and the obligation, to ensure that the outcome of the Syrian Civil War looks like Libya, not Lebanon.