Sons of Liberty International (SOLI) is the first security contracting firm run as a non-profit. SOLI provides free security consulting and training services to vulnerable populations to enable them to defend themselves against terrorist and insurgent groups. SOLI was founded in response to the deaths of my friends James Foley and Steven Sotloff, who were beheaded by ISIS in Syria in 2014. Having witnessed the failure of the international community to deal with security crises involving authoritarian regimes and terrorist groups, it became apparent that a non-state initiative could be instrumental by stepping in where the international community failed.

SOLI began operating in Iraq in December, 2014 with a covert training program for the Nineveh Plain Protection Units (NPU), an Assyrian militia of Iraqi Christians, and by closely advising NPU leadership. In January and February, 2015 training was moved to a Peshmerga base with permission from the Kurdistan Regional Government and the training was expanded to the entire NPU battalion of over 300 men. This was followed by a third training, a leadership program in May, 2015 for NPU sergeants and officers. This third and final training program for the NPU was recently covered in the longest feature article Maxim magazine has ever published, Exclusive Report: Meet the American Taking the Fight to ISIS.

The Iraqi government, recognizing that the NPU is now a trained and capable force, will begin integrating the NPU into the coalition against ISIS. Our mission with the NPU successfully completed, we will soon begin working with another Christian force in Iraq to assist them in similarly integrating into the coalition against ISIS.

In assessing our experiences over the past several months, we have learned a lot from our work with the Assyrians in Iraq:

- The Assyrian community in Iraq is exceptional. Demographically, the Assyrians of Iraq tend to have higher levels of education and per capita income than Iraq as a whole. Their work ethic is also more Westernized than the general population. This has made them ideal candidates for training, and they learn much more quickly than other forces being trained in Iraq.

- The morale of the Assyrians exceeds that of other forces in the region fighting against ISIS. Assyrians are eager to defend their homeland (the Nineveh Plain region of Iraq) and recapture territory lost to ISIS. The NPU has over 2,000 volunteers; their limitation to a battalion sized force is due to a lack of funding and supplies to field a larger force at this time. NPU soldiers requested morning physical training, studiously took notes during classroom instruction, and were eager to participate in all-day, difficult training sessions.

- Assyrians are excellent students for training. Having been denied the right to field their own military force in recent years, most NPU soldiers were recruits with no military knowledge or experience. They were eager to learn and train, and did not have poor previous instruction that needed correcting. We had no problems with egos, overconfidence, or know-it-all attitudes that can occur when training young men for combat. The NPU leadership, even those with previous military experience in the Iraqi army, were also eager for our instruction and advising, and were a pleasure to work with.

- The Assyrian community is less xenophobic than other regional minorities. Assyrians in Iraq recognize the need to form coalitions with other minorities in Iraq for mutual benefit and survival. The NPU is open to all Iraqis of the Nineveh Plain region of Iraq, and hundreds of Yazidis have already expressed an interest in joining the NPU.

- Assyrians should be utilized by the West in the fight against ISIS. Unlike the Kurds and Iraqi government forces, the Assyrian forces do not receive any Western support. Until recently, they were largely dependent on donations from the Assyrian diaspora community, and some Assyrian forces still are. Not supporting Assyrian forces in Iraq has been a serious miscalculation by Western governments, largely due to a misplaced fear of stoking sectarianism or following the desires of the majority Kurds, Sunnis, and Shias who fear an armed Assyrian Christian force in Iraq.

We at SOLI are very optimistic about the Assyrian forces playing an instrumental role in the fight against ISIS and in post-ISIS Iraq. However, there are challenges facing the community that should be addressed:

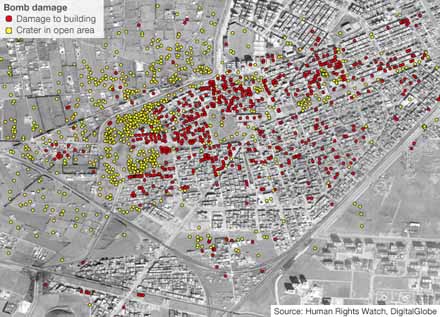

- The Assyrian community is not unified. Political divisions among the Assyrian Iraqis are devastating to their ability to form a unified, cohesive force capable of providing security for the Nineveh Plain region of Iraq. There are at least four major Assyrian forces operating in the Nineveh Plain region alone – the NPU, Dwekh Nawsha, Nineveh Plain Forces (NPF), and the Tiger Guards. Each is associated with an Assyrian political party or with the Kurdish Peshmerga. A SOLI attempt to initiate discussions between two rival militias to unify them in May, 2015 was rebuffed by both sides. As in other regional conflicts, most notably Syria and Libya, divisions are increasing as time progresses, and a unified Assyrian army remains an elusive dream. A unified Assyrian army should be the goal of all Assyrian forces in Iraq, as this is the only hope of resisting Arab and Kurdish aspirations for annexing Assyrian lands.

- Assyrian forces are plagued by interference from outside groups. This became evident early in our work with the NPU when two small organizations in California began issuing false statements to the Assyrian community and lying to the media about the relationship between the NPU and SOLI. Worst of all, these two groups in California even went so far as to repeatedly interfere with the training of the NPU. It is imperative that the leadership of Assyrian forces resist all attempts by outside groups to influence them – this is a duty they owe to the brave men they are leading in combat and to the Assyrian community at large who are depending on these Assyrian forces to protect their ancestral homeland. We praise the NPU leadership for having the courage to largely resist the influence of outside groups, even when repeatedly threatened by these groups that funding to the NPU would be cut.

- There is a disconnect between Assyrian forces on the ground and the diaspora community. The disinformation campaign of Lazar and Gardner was believed by a surprising number of Assyrians outside of Iraq, who repeated and even embellished the false information. This problem was exacerbated by the existence of false Twitter accounts like @AssyrianDefense which portray themselves as belonging to the NPU when they do not (the NPU’s only Twitter account is @NinevehPU), and individuals outside of Iraq falsely claiming to be spokespersons of the NPU. Such statements by third parties should be disregarded, as this has caused great confusion and a loss of confidence in Assyrian forces on the ground in Iraq, which has led to reduced donations to support the forces and potential complications for these forces when seeking international support.

Official NPU document about the NPU’s great relationship with SOLI and stating that outside groups do not speak for the NPU

Despite these concerns, what we at SOLI have observed in working with the Assyrians of Iraq over the past several months has reinforced our confidence in the Assyrian forces to become one of the most important factors in the fight against ISIS and in the future security of Iraq.

In conclusion, SOLI has had an excellent experience working with the NPU and we congratulate them on their success. We look forward to working with additional Assyrian forces in Iraq to help enable their inclusion in the coalition against ISIS. We have great confidence in the Assyrian people and will continue to work hard for their noble aspirations of security and self-determination.

Long live the Nineveh Plain