Mali, Sudan, and Ethnic Conflict in Northern Africa

(also available in French here)

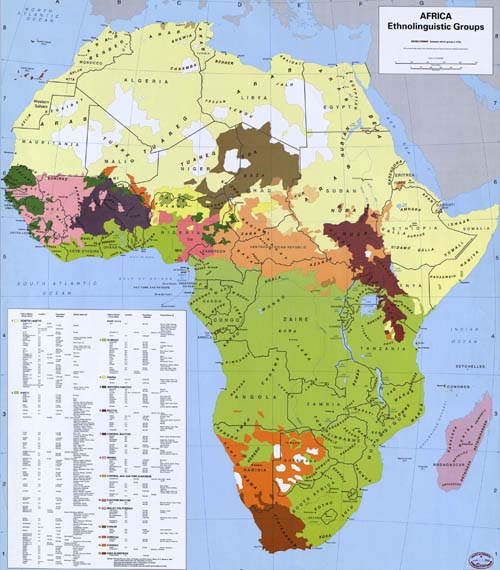

Africa, for all its beauty and rich history, has always been a complex and often harsh continent. Hundreds of ethnic groups, some of which have hostilities that date back millennia, live in largely impoverished conditions in a forced co-existence dictated by colonial-era national borders.

Ethnic groups in Africa

One of the clearest examples of ethnic and racial tension in Africa is the conflict between Arabs (and the Tuareg, who are Berbers) and sub-Saharan (black) Africans. For over 1,000 years Arabs enslaved black Africans; estimates of the victims of the Arab slave trade range up to 18 million. Although the Arab slave trade began to rapidly decline in the 1960s Mauritania did not criminalize slavery until 2007 and even today tens of thousands of Africans remain enslaved through bonded labor or other forms of slavery in the region (it is estimated that 8% of Nigeriens and 10-20% of Mauritanians are slaves). Beyond this predatory relationship, interaction between Arabs/Tuaregs and black Africans was somewhat limited by the vast expanse of the Sahara desert which acted as a natural buffer zone.

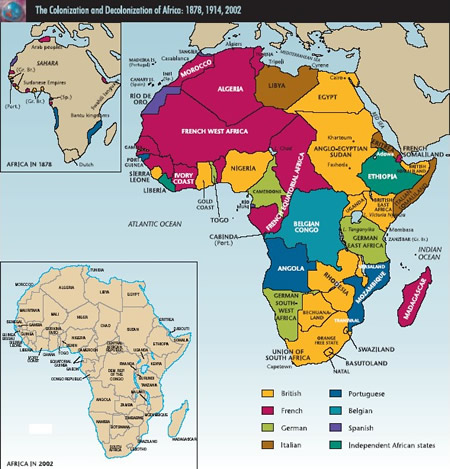

That began to change in the 1800s during the “Scramble for Africa” when European powers colonized and carved the continent into what became (for the most part) the modern national borders. Arabs, Tuareg and black Africans were lumped together in a band of French and British territory stretching straight across the southern expanse of the Sahara that later became the current states of Mauritania, Mali, Niger, Chad, and Sudan.

How the European Colonialists Created the Borders of Africa

In the past decade four of these countries (Mali, Niger, Sudan and Chad) have experienced rebellions or civil wars fought predominantly along ethnic or racial divisions. This is not to suggest that ethnicity and race are necessarily the root cause of these conflicts and that the racial conflict was inevitable, but the role of ethnicity and race cannot be dismissed either. The ethnic and racial animosity that exists is very real and apparent to anyone who has spent time in the region. These wars occurred for a multitude of standard reasons – politics, resources, religion, history – but it was often quite clear that ethnicity and race were determining factors when the locals chose which side to fight for.

The latest Tuareg rebellion in Mali claimed the desert north of the Niger River as the independent state of Azawad in 2012, separating the Tuaregs from the black Africans in southern Mali. The previous Tuareg rebellion (2007-2009) occurred in both Mali and Niger with the Nigerien Tuaregs demanding decentralization and that the Nigerien military in their territory be dominated by Tuaregs instead of black Africans. Sudan fought two civil wars between the Arab-dominated north and the black African south, the most recent from 1983-2005 which resulted in autonomy and later the independence of South Sudan in 2011. The Sudanese Civil War spilled over into Chad from 2005-2010 as mostly a proxy war between Sudan and South Sudan utilizing the same ethnic militias from the Sudanese Civil War.

Mali, Niger, Sudan and Chad should never have existed in their current form and the redrawing of borders in Mali and Sudan is long overdue. There may unfortunately never be any widespread reconciliation between Arabs/Tuaregs and black Africans given the history of slavery, racism, discrimination and competition for resources in combination with literacy rates that are among the lowest in the world (a substantial obstacle to education programs designed to foster racial harmony). Black Africans have been continually victimized by their Arab and Tuareg neighbors in Northern Africa for over a millennium, resulting in a hatred and fear that is deeply engrained. Religious (generally Muslim vs Christian and animist) and cultural differences further exacerbate the situation.

Sudan and South Sudan are now on the brink of war after less than a year of separation, feuding over border demarcation and oil revenues. Both sides are using proxy rebel forces and Sudan has conducted air strikes against targets in South Sudan. If history is any indication, the violence will slowly but surely spill over into Chad as rebel groups conduct cross-border raids. It is also likely that Uganda will intervene militarily and fight alongside South Sudan if necessary. This would escalate the conflict into looking very much like a disturbing, regional race war.

In Mali the Tuareg rebellion is far from over. As the Tuareg celebrate their declaration of the newly independent state of Azawad counter-revolutionary forces are assembling into militias of their own and revenge is at the top of their agenda. One of my sources has told me on good authority that at least some of the militias are debating whether killing off the Tuareg fighters will be enough or if they should also execute the Tuareg women and children to prevent yet another Tuareg rebellion in the future. The rest of the war won’t be fought by the Malian army and the Tuaregs, but by disparate militias that will rack up a list of human rights abuses that will dwarf those that occurred during the Libyan civil war.

What is coming will shock the world.

The only way to prevent these horrific outcomes in Mali and South Sudan is aggressive diplomatic intervention by the international community to force a settlement of hostilities. Such negotiations must result in a legitimate separation that allows for self-determination by both sides. In Mali this would mean allowing either the independence of Azawad or legitimate, federal autonomy. The current conflict between Sudan and South Sudan is fairly straightforward (it’s about oil) and can be negotiated; however, the only long-term solution is for South Sudan to construct another pipeline that will free it from dependence on Sudan. The mutual reliance designed to prevent conflict – South Sudan has the oil but Sudan has the pipeline to transport it – will only cause future conflict. When China finally chooses a side (it supplies Sudan with weapons yet imports oil from South Sudan) and agrees to construct a pipeline in South Sudan that allows for the export of oil through Kenya, a permanent peace will become possible. Reconciliation between the Arab north and the black African south is not possible after two civil wars that left over 2 million dead.

Unfortunately, it is far more likely that the Mali and Sudan wars will continue to escalate. President al-Bashir of Sudan has vowed to fight the South Sudan “insects” who “do not understand anything but the language of the gun and ammunition” and Mali’s President Traore is threatening “a total and relentless war” against the Tuareg. The only potentially positive outcome is that these wars will be so devastating to all involved that they result in the Arab/Tuareg and black African conflict being finally settled when, desperate to prevent this from recurring, both sides genuinely separate and wage their conflict purely on political and diplomatic fronts, from a distance. This is the only solution that will fully respect the principle of self-determination and the only permanent one given the amount of bloodshed over the years.

The question is whether Niger and Chad, trapped in the middle of these two wars and having their own history of ethnic and racial conflict, will escape the turmoil unscathed. If history is any indication, they won’t.