Escape from Abu Salim Prison

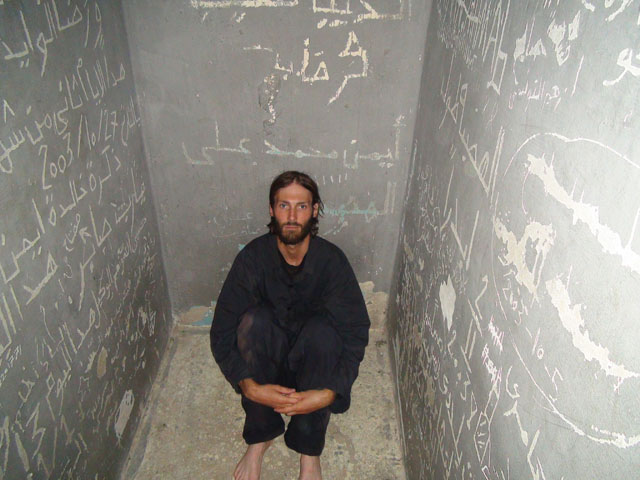

One year ago today I escaped from Abu Salim prison in Libya. I had spent half a year being psychologically tortured in solitary confinement, pacing in my cell, staring at the walls and fearing that this would be all I would know for the rest of my life.

On the 165th day of this unimaginable hell, prisoners came to my cell and broke off the lock. I escaped Abu Salim with other prisoners of war and we ran for our lives.

That night I was watching the story of my escape on CNN.

The world thought I was dead for most of the time I was in Abu Salim prison – I was missing in action. Despite the widespread belief that I was buried in the desert, Human Rights Watch (HRW) advocated for my release and the international press covered the story. Only in the last two weeks before my escape did the Gaddafi regime even admit that I was alive and in custody, but they still would not let anyone see me or check on my condition.

HRW went to Abu Salim a few weeks before the prison break and was told I wasn’t there. I was there, and I was being held in solitary confinement under deplorable conditions. The Gaddafi regime did not care what the US government, NGOs, or the international press had to say. I would still be in that cell, if not executed, if we hadn’t won the war.

I had come to help the Libyan rebels, and then the Libyan rebels came to help me. My fellow rebel prisoners broke me out of the cell and we escaped together. There was no outside intervention to save me from the horrors of Abu Salim.

A few days after my escape, I was at the Corinthia Hotel as a guest of the rebel government and I came under intense pressure, especially from HRW, to leave Libya. The international press started calling my mother telling her to convince me to leave as well. The press was confused about why I was still in Tripoli days after escaping from Abu Salim prison, as if I was waiting for something.

I was waiting for something – for Nouri. Nouri Fonas was my friend of four years with whom I had been serving in the rebel forces before I was captured. Transportation was difficult and it took Nouri a few days to arrive from Benghazi. Soon after he arrived, we left Tripoli together.

The press and HRW had no idea where I went. They assumed I had conceded to their demands and gone home.

Instead, Nouri and I spent one night in Benghazi, paid a visit to the Ministry of Defence, and then headed back to the front line. We joined the Ali Hassan al-Jaber brigade, were assigned a military jeep that we fitted with a DShK heavy machine gun, and returned to the war.

Just as when I first joined the revolution in March 2011, nobody was supposed to know about my return to the front lines. My participation in Libya’s revolution was supposed to be a secret, a personal matter, but being captured and imprisoned in Abu Salim erased my anonymity. I tried once again to stay below the radar when returning to the front lines after prison until a photographer spotted me as I passed through a checkpoint in the jeep. The secret was out.

It was for the best, it turned out. Occasionally, I was able to take the press with me in the jeep to the front lines so they could report on the war while I fought in it, giving them a safe escort in an otherwise uncertain conflict zone. And thanks to our commander giving Nouri and I a lot of freedom to move as we wanted and fight where we wanted, we had a rare grasp of what was happening on the various front lines in Sirte. We fought at many different areas on the front lines alongside various other brigades, making us a reliable source of information for the media.

Nevertheless, I was criticized after the war by men incapable of understanding why someone who endured nearly six months of hell in the notorious Abu Salim prison would return to combat after escaping. To this day some of these individuals, from the comfort of their homes in Europe and the United States, have tried to disparage me for keeping the commitment I made to Libya the day I first put on a uniform in March 2011.

Their criticism speaks volumes about their character, not mine. I told the rebels when I joined them in March 2011 that I would not leave Libya until the country was free. I honor my word; that is how I was raised. I would also not leave Libya before the men I was captured with were accounted for – they could have been in prison in Sirte or another Gaddafi-held city. Why would I ever abandon them? Furthermore, how could I leave Libya when there were any prisoners of war still being held by the regime?

These wars of liberation aren’t a game and there aren’t any timeouts. The war in Libya, and the war now raging in Syria, are all-or-nothing pursuits. As Omar Mukhtar said, “We will not surrender. We win or we die.” As I write this, there are thousands of prisoners waiting in their cells in Syria, just as I was waiting in a Libyan prison last year.

No amount of reporting, NGO press releases, or rhetoric will get them out – Bashar al-Assad doesn’t care what anyone says, just like Gaddafi didn’t care what any of them said about me.

This isn’t the time for observation. This isn’t the time for politely discussing the situation at the UN, or standing at podiums issuing idle threats about what might happen if lines that we keep moving are somehow crossed. We are way past going through the motions of diplomacy.

Those thousands of Syrian prisoners – men, women, and children- are waiting for us. Each day they stare at the walls and wonder if it will be their last. I know the feeling, and I’ll do whatever I can to help them escape from their Abu Salim.

And I’m starting with this film.