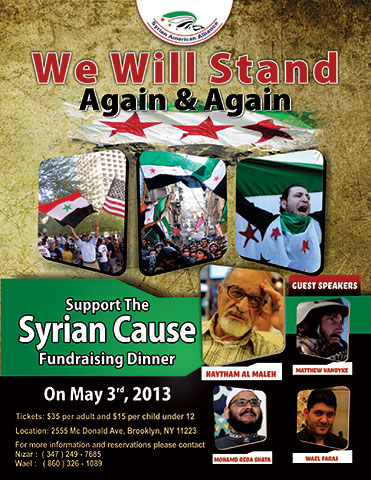

Freedom Fighter Matthew VanDyke's Speech at a Syrian American Alliance Fundraiser in New York

May 3, 2013

Thank you for inviting me to come speak to you today about the Syrian revolution. My perspective and involvement in Syria is a bit unconventional, so I’d like to begin with explaining a little about my background and what led me down this path.

In 2004 I graduated with a Masters’ degree in Security Studies with a Middle East Concentration from the Georgetown University School of Foreign Service. Most of my classmates went on to work for the CIA, FBI, DoD, State Department, or Think Tanks. I took a slightly different course.

From 2007 to 2010 I traveled from Mauritania in West Africa, all the way to Afghanistan, across North Africa, the Middle East, and Central Asia by motorcycle, to make two motorcycle adventure documentary films. Most of my time was spent in the Arab world, including in Libya and Syria.

Three years later, in February 2011 I was talking to my Libyan friends online and they were telling me that their family members, their friends, and their neighbors were being arrested, tortured, injured, and killed. They feared for their lives, but they were demonstrating and fighting Gaddafi in the streets everyday for their freedom, despite the danger.

One of my Libyan friends said to me, as their situation began to look increasingly dim, “will you tell your friends about me if I die?” This had a tremendous impact on me. A few days later he asked me the simple, powerful question: “Why doesn’t anybody help us?”

I made the decision that day to go to Libya and help my friends.

How could I sit back and do nothing while my friends and their families died in the streets of Tripoli, simply for their desire to live as free men? I could not abandon them when they needed help.

I went to Libya and joined the rebel forces very early in the revolution, before NATO became involved. I know how Syrian fighters are feeling because at that time, before NATO’s involvement, we had no support from the outside world and were actually in a worse situation than the FSA is right now in Syria because we weren’t yet getting supplies or assistance from outside Libya at all. We had fewer weapons, fewer men, and far less organization, in those early days of the Libyan revolution, than exists in the Syrian revolution today.

But the few of us who were willing to fight at that point went to the front lines, and I was captured by Gaddafi’s forces while on a reconnaissance mission. I spent nearly six months in solitary confinement in two of Libya’s most notorious prisons, Maktab al-Nasser prison and Abu Salim prison. In those months I got a personal taste of what prisoners of war and political prisoners have faced under these regimes for decades. I wasn’t told what I was accused of, I wasn’t allowed communication with the outside world, and at times I could hear men being tortured in other parts of the prison. The Gaddafi regime told the international press, NGOs, and the US government that they did not have me, wanting the world to think I was dead.

After nearly six months in prison, there was a prison break at Abu Salim and prisoners came to my cell and broke off the lock. We ran from the prison together and escaped. I waited in Tripoli for one of my Libyan friends to come from Benghazi, then I went with him back to the front lines.

I joined the new rebel army, the National Liberation Army, which hadn’t even existed as an organized military when I was captured by the regime several months before. I was issued a Libyan rebel military ID card and assigned a military jeep. I became a Dushka heavy machine gunner, and my Libyan friend, Nouri, whom I had known for 4 years, was the driver. We also fought as infantry, including in urban combat. During the war I had around 40 engagements with the enemy, mostly in the Battle of Sirte.

After the war was over, I returned to the United States, and turned my attention to Syria. Some Libyans soon went to fight in Syria, and I nearly went with them. The reason I did not go was because the Syrian rebels had enough men at that time, they just lacked weapons and ammunition. I knew that before I would go to fight, I needed to do something to help get more international support, and financial support from outside Syria. So I made the film that you will see tonight, which was designed to show audiences in the United States and Europe who the Syrian rebels actually are, and why they are fighting the Assad regime. Most importantly, however, I directed it in a very calculated way to maximize its effectiveness for fundraisers and other events that can have a tangible affect on the ground in Syria.

My participation in the Libyan revolution was very personal because of the close friendships I had developed over the years with Libyans. I had been to Syria 3 times before the Syrian revolution, but I did not have good friends there (although I have some there now). Libya was personal and ideological for me, but Syria is mostly ideological.

Yes, of course I care about Syria and Syrians. But I don’t have any deeply rooted personal connection to Syria. I don’t have close friends there. I am not a Syrian-American, I’m not even an Arab-American. I’m a Christian white guy.

Syria doesn’t mean the same thing to me as it means to Syrian-Americans, and I’m not going to pretend that it does. Perhaps that will change if the time comes that I fight and shed blood for the country, as I did in Libya, but as of now I fight for an idea.

The idea that all men and women, regardless of race, ethnicity, religion, or where they live in the world, are entitled to liberty. I believe in this so strongly that I have joked with my Syrian friends that I am the Jabhat al Nusra of liberty, that as strongly as Jabhat al Nusra believes in their interpretation of Islam and other beliefs that motivate them to fight in Syria, that is how strongly I believe in the concept of liberty.

Americans need to take a moment of self-reflection, something I became very good at while sitting in a prison cell for six months, and ask ourselves why in the 21st century we’ve abandoned so many people around the world to live under authoritarianism, including 20 million of them in Syria. We’ve put a man on the moon, yet all around the world we still have people living under medieval forms of government.

It is a moral imperative that we bring them into the 21st century with us. We cannot leave anyone behind. They’re waiting on the front lines. They’re waiting in the prisons. And they’re waiting in their homes, old men who have spent their entire lives under oppression, who just want to know before they die that their children and grandchildren won’t suffer the same fate that they have.

They’re waiting for us. In Syria, in Iran, in other countries of the region, in Africa, in Asia, all around the world. They shouldn’t have to wait any longer. They shouldn’t have had to wait this long. I’ll be ashamed if my grandchildren grow up in a world where leaders glorify themselves by putting their own faces on the money, or put people in prison for their thoughts or words. I’ll be ashamed if my grandchildren grow up in a world where they know of authoritarianism from anything other than history books.

We’re at a pivotal moment in history. Just as civilization started in the Middle East, just as many of the world’s major religions started there, so has the final wave of revolutions that will finally liberate mankind. They’ve called it the Arab Spring, but it isn’t an Arab Spring, it’s a Human Spring. And like dominoes the regimes will fall, one after another, each one weakened by the fall of the one before it, and each people inspired by the victory of their brothers in the revolution before theirs.

This is why Syria is so important to me and important to the world. Egypt and Tunisia were the first two dominoes. Libya was the third. But Libya was the first domino where we showed the world that armed revolution is a path to liberty in the 21st century, as it had been for America and much of Europe in the past. Syria is the next domino to fall.

Why am I telling you all this? Because there are others in this country who feel the same way, and we need to bring them into the movement. The Syrian-American community has been active for the past 2 years, and many of you have given all you can. The money is running out. People are getting discouraged. Some of you are starting to feel like the rest of America has abandoned us.

But we need to ask ourselves, have we really reached out to them? How many non-Syrian Americans are here tonight? Not many. This is a small tent. It is time to make it bigger.

I’m proposing that we make a substantial effort to broaden our base of support in this country, to reach out to non-Syrian Americans who believe, as I do, in liberty as a universal concept and right. You can appeal to their morality, their conscience, even their patriotism as Americans to get them onboard with this cause. But we have to actively approach and engage them.

When I was in Aleppo a few months ago making the film, the regime called me a terrorist and broadcast my name and photos of me on the Syrian State TV channels, telling millions of Syrians that I was a terrorist who had come to join the FSA.

They call us terrorists, we call them terrorists, it doesn’t matter. We all know that the vast majority of Syrians fighting in the revolution are fighting simply for freedom and liberty, to choose their own leaders and determine their own future. I talked to many fighters in Aleppo when I was there, and virtually all of them said the same thing – they simply want the fall of the Assad regime.

They want freedom and democracy. These are American values. Why then do we continue to just preach to the choir at event after event, passing the collection plate back and forth among friends and colleagues?

Where are the new faces? Where are the college students? Where are the US veterans? College students and US military veterans contact me every week asking how they can help Syria.

The fact is, there is a potential pool of supporters for our cause that dwarfs the Syrian-American community. If we had been really reaching out to them for the past 2 years, Syrian-Americans might actually be the minority at these fundraisers instead of guys who look like me. The band and I are the only non-Syrian-Americans here tonight.

We’ve done a very good job of tapping our networks around the country to support the cause, but that’s not going to be enough now that the war is dragging on. And while I hope I am wrong, I believe that this war could go on for years.

The Syrian-American community has given so much to the cause, and many of you have given all you can. This revolution needs a lot more supporters outside the Syrian-American community if it is going to succeed.

We need to mainstream this revolution, and quickly. We need the college students and the military veterans. We need church and school fundraisers. We need rotary clubs and other community organizations helping. We need punk bands and hip-hop artists holding benefit concerts. We need not just the demographic that watches MSNBC, but also those who watch MTV.

We cannot do this ourselves. The Syrian-American groups are relatively new, and the Arab-American groups have historically faced difficulty influencing policy outcomes in Washington, DC.

That said, the Syrian-American organizations have done an extraordinary job the past two years. The tremendous work and sacrifices that you have all made the past 2 years is truly admirable and has made a significant difference on the ground in Syria. The revolution would not have achieved as much as it has without the support of your community here in the United States.

But now that the war is continuing, with no end in sight, we need to pursue additional strategies. Expanding this movement to include more people is essential to garner both political and financial support.

The Syrian revolution to me is simply about liberty. There are many Americans who feel the same way. I know because they contact me all the time wanting to help. Liberty is a universal concept. It is a foundational American concept.

I hope that all of us can work together towards achieving victory in the revolution and liberty for Syria, with the help of a larger community of fellow Americans.

Thank you.

A working version (not the final version, which was saved for film festivals) of Matthew VanDyke's Syria war documentary film "Not Anymore: A Story of Revolution" was shown to the audience at this event.